Post-consumer waste has been under central discussion of the circular economy in fashion industry for the last 5 years. Same time, RR team has been mainly working on building statistics and data to estimate the volumes of industrial waste from fashion production. Any public data about this matter is globally unaccessible. However, based on the research we’ve done mapping out the post-industrial waste in 20 countries, we can make some estimates.

Different studies give different estimates on the total number of garments produced globally, falling between 80 billion to 150 billion pieces a year, before the corona crisis hit. “The 2020 Preferred Fiber and Materials Market Report reveals that the global fiber production has doubled in the last 20 years, reaching an all-time high of 111 million metric tons in 2019 and pre-COVID-19 results indicated potential growth to 146 million metric tons by 2030.”(1) Not all textile fiber gets used in fashion, but by an estimate at least a third of it does, given the volumes of new garments produced globally.

From our research (read our white paper here) we also know that up to 47% of all fibre entering the fashion value chain becomes waste throughout the myriad of different stages of production from fiber, yarn, fabric up to a garment (2).

However, the wasted material of a process can be usable in another. For example, it should just be obvious that comber noil, the long fiber falling out of the spinning in the first round of finer yarns, can be taken back to spinning and used again for production of coarser sweater yarns.

In such a way we can create a whole hierarchy of waste based on the market value or the quality of (recycled) products that can be made out of them. By the market value it ranges from close to the same price of raw material down to negative value – pay extra for it so that we incinerate or landfill it for you. Same with quality – knit yarn waste is better for recycling than fine shirting fabric waste for example. Market price and quality aren’t however always the best indicators of hierarchy, because depending on the location of the waste and different market barriers the same type of waste may end up finding a completely different use case in different markets. A more general match of waste types and existing recycling technologies should be applied globally.

So if we leave out the location, theoretical borders between organisations and the access to best recycling technologies, what should we even call waste? Where to draw the line?

Taking a similar approach to the Global Recycling Standard, we could claim that half of the spinning waste and most of the overstock and deadstock fabrics from mills and garment factories are so highly reusable that they should not be considered “waste”. It can be used in-house and the reuse of such waste should be qualified as process optimisation, even if it sometimes takes extra effort, investments or marketing to do so. We should also consider that roll-ends and large cut panels usually find their way from larger production sites to smaller factories nearby, and are a classical by-product of mass-production. We can then rather conservatively say that the fashion industry still generates 25% of such textile waste that needs pre-treatment before it could be used again as a resource for next round of fashion production. Let’s call this recyclable textile waste.

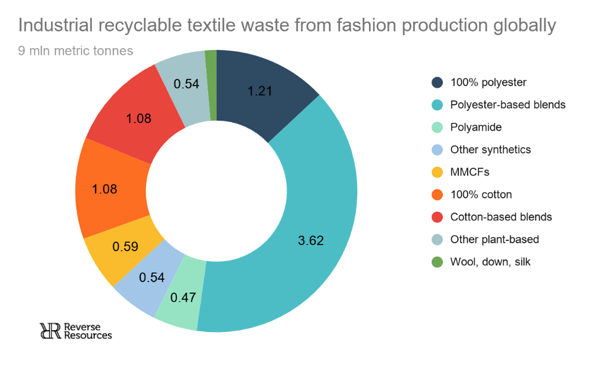

In conclusion – from 37 mln tonnes of fiber used by fashion and 25% of that becoming recyclable waste – we can conclude that the total volume of industrial recyclable textile waste is at least around 9 million tonnes globally per year.

We took it a step further. We looked at the breakdown of fibers by composition reported in The 2020 Preferred Fiber and Materials Market Report by the Textile Exchange, and compared this with the data from the waste mapping surveys done by Reverse Resources in 20 countries across 1200+ factories. Based on that we have put together a rough indication of which fibre compositions and types of waste are available in the global market for textile recycling.

This is a lot of waste generated each year. It is much more than what the industry has been expecting while focusing on the challenges of post-consumer waste management. Post-industrial waste, however, is very homogeneous in terms of compositions, colours, chemical background. In the light of new emerging recycling technologies searching for a good fit with the feedstock they could use, post-industrial waste is a low-hanging fruit to scale up production of such recycled yarns and fabrics which indeed could start replacing raw materials for fashion, and close the loop of circulation.

Of course, a lot of this waste already does get recycled. The question really is – is it in fact finding the best new life-cycle for itself, the best match with the recycling technology that can turn it into the best possible raw material again? 80% of recyclable waste does not get segregated by composition or waste type in production, and needs to be manually sorted. When passed to collectors and traders, 40% of the waste really gets discarded (landfilled or incinerated) due to a too high contamination or mismatch with buyers due to price, location or lack of market insight. It means that the majority (~70%) of the post-industrial textile waste is probably finding some next life-cycle thanks to the collection and trading system, but there are currently no means of tracking down where the waste is actually ending up at. We do however know that almost all of this waste is flowing to other industries (industrial symbiosis), and not back to fashion as a raw material for next cycles of the fiber circulation. Not yet at least.

Let’s take a quick look at post-consumer textile waste for comparison. 11.9 million tonnes of post-consumer waste is generated in USA alone (including clothing, sheets, towels; excluding footwear, furniture, carpet)(3), which would mean 84 million tonnes of waste per year if we expand this on global population with same consumption rate to simplify the calculation. To simplify things, this does not yet consider that US probably has much higher use of textiles per capita compared to most other countries. If 30% of that gets collected separately (most probably much less) out of which half can be potentially resold, we can estimate that globally maximum of 12 million tonnes of post-consumer waste could be made available for the textile recycling industry as a feedstock. However, post-consumer waste is very heterogeneous flow of textile fibers with a large number of challenges around collection, sorting, identifying compositions, logistics, etc.

With the EU push on separated collection of post-consumer as well as the emerging technologies around identifying the compositions of garments in manual sorting, we will start seeing the increase of more homogeneous volumes of textiles becoming available to the market over the coming years. But if our goal is to support the emerging smart textile recycling technologies to close the loop of fashion own waste and reach 100% circulation for the industry by 2030, we need to look at both post-consumer and industrial waste streams hand in hand. We need to develop the hierarchy of waste flows in comparison to best technologies globally as a holistic and systematic concept.

We will give more insight into the textile recycling industry current situation and developments – the demand side of the textile waste – in our next blog posts. Stay tuned!

References:

(1) The 2020 Preferred Fiber and Materials Market Report, Textile Exchange: https://textileexchange.org/2020-preferred-fiber-and-materials-market-report-pfmr-released/

(2) Reverse Resources White Paper (2017): www.reverseresources.net/white-paper

(3) Revolve: https://www.revolvewaste.com/